Her father dreamt of a united Englaland. That dream, however uncertain it remained, began now.

The white stag on the green banner soared above the battle-hardened thegn. He led the shield wall from the centre so that the men could always see his large frame, but to do so came with great risk. If he should fall, then the ship they were leading into those dark strays would become rudderless.

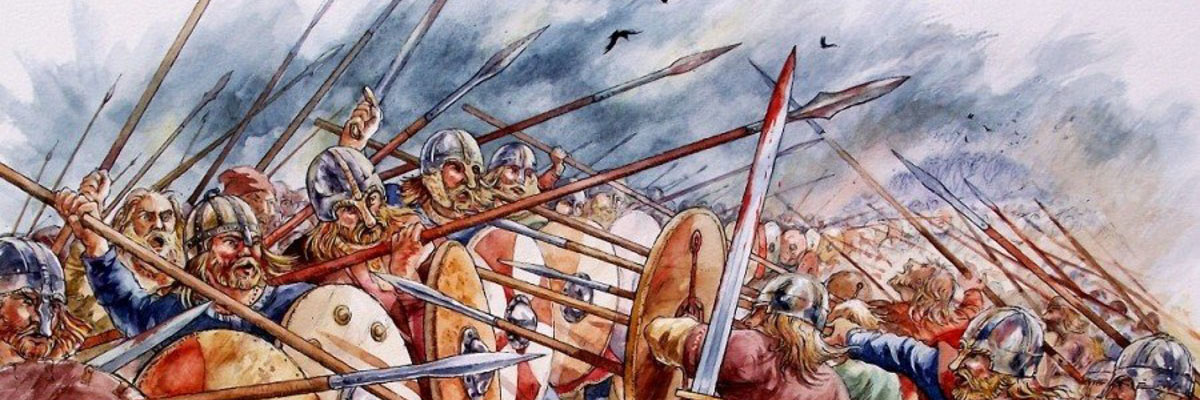

The Norse formed up into a shield wall of their own. Shield rattled upon shield to create a bright-coloured wall of spiral patterns and mythical beasts of old. The butted rings of chainmail glistened like morning dew in the sun as the wealthiest and strongest men stood at the centre of the shield wall. Those who wore leather or simple linen garments, for even cloth was preferable to bearing the brunt of a blade swipe on bare skin, gathered on the flanks or in the rear ranks of the Norse assembly.

Bearded men with weather-beaten faces bellowed wildly and slapped their axes and spear blades against their shields.

They begged Ingimund for the moment of attack.

But the jarl did not budge. Not yet.

‘Stand!’

Wulfric’s command bellowed across the field and reached Æthelflæd’s ears. She observed as the Saxon shield wall halted its advance and presented an easy target to the Norse, outside bowshot of Ceaster’s red sandstone walls. The men braced themselves with their shields and spears overlapping, a brave reflection of the onlooking Norse, and awaited the moment of trial.

The Norse jeered in response. They believed that Odin himself had presented them with a ready-made meal on a wooden platter. They replied to Wulfric’s challenge by shouting insults and blasphemies, but the veteran thegn kept his men silent and brooding.

‘Keep your energy, lads,’ he shouted above the din. They would need it.

A hundred Norsemen had gathered for the initial assault in the shield wall, while hundreds more milled about the encampment, donning armour and weapons, and many watched more as curious onlookers than participants in battle. They did not believe the Saxons, being comprised of so few men, could challenge them.

Æthelflæd caught sight of Ingimund watching the scene unfold with great interest.

The jarl must have wondered as to whether foolhardy heads led the Saxon foray, or if faith in their god, the nailed man to the cross as the Norse had once proclaimed, had driven them to sacrifice rather than submitting to him. He indeed suspected a ploy, but he gave no indication as more men heaped behind the Norse shield wall and prepared to do battle before Ceaster.

‘God, forgive my despair, but there are many of them,’ Cenhelm stirred beside Æthelflæd. ‘Will the ealdorman send more men, lady?’

The worry in the young hearthguard’s voice betrayed his otherwise calm demeanour. He shifted his feet, shield arm first, and sword at the ready. Ceaster’s walls were an imposing sight of Roman engineering, measuring thirty feet high, but a determined army could breach them and quickly overrun the town’s meagre garrison.

‘Courage and faith, Cenhelm,’ Æthelflæd responded coolly.

‘Help will arrive soon enough, but until then we must not forfeit our reason for despair.’

‘You are right, lady,’ he exhaled. ‘But I fear our beloved Mercia is assailed more every year. When will fortune turn in our favour? May God keep us!’

‘Yes, God keep us,’ Æthelflæd repeated as if to conceal the tightening ball in her throat.

She flicked a glance over her shoulder to the south-east, toward the village of Huntandūn, and hoped to catch Æthelred and the fyrd marching up the road toward them, with the sun reflecting off their spearheads and mailed coats like shards of smelted silver.

But there was no one, and the road was empty.

They were alone.

Æthelflæd clasped the gold and gem cross hanging around her neck and her eyes hardened. The men she had brought from Gleawceaster, all fifty of her personal hearthguard, were all that could be spared, but she made no such remark outside her own thoughts. There was no looking back now, and no one was coming to their aid.

Her father dreamt of a united Englaland. That dream, however uncertain it remained, began now.

They would defend Ceaster with blood-stained tears, or they would perish.

Nervous excitement mingled with the rippling banners of both armies, while the hungry grating of ravens circling above goaded the two armies into slaughter.

The Saxons, their scieldweall comprised of Æthelflæd’s personal hearthguard and a number of well-equipped ceorls, seemed alone; a stray sheep plucked from the safety of its pen and sprung upon by ravenous wolves.

There was an uneasy bind in Æthelflæd’s chest, a sour feeling opening up her insides, and her breaths laboured, hard and short.

She gripped the stone crenel, as if by doing so could she fasten a favourable outcome to her whitening knuckles. For that fleeting instant, the fragile lull that advanced ahead of the storm, it seemed as though those red sandstone walls, built by the Romans to outlast centuries, were all that stood before the Norse. Even with Wulfric and his men assembled on the field below.

But could they outlast Ingimund?

A lone war horn groaned from the direction of the Norse encampment.

It was a mournful melody imbued with the terrible anger of the old gods, for the Saxons had abandoned the ways of their ancestors. Even they had arrived from a foreign shore at some point in time to invade and settle these lands. Now vengeance had arrived through the invocation of Odin’s divine judgement. His heralds leapt forth from the linen sigils of a dozen banners, snarling wolves, vicious serpents, and ravens in full flight, who dared the Norse forward to greet the Christians with fearless resolve.

There was a deafening roar from the advancing Norse.

Men garbed in chainmail or leather marched abreast, several ranks deep, so as to present a single unbroken front. Spears and shields were interlocked to form an imposing wall of blades, like the deadly spines of a hedgehog. They did not rush headlong, as one observing from the surrounding fields might expect, but with deliberate intent, their movements well-drilled.

Æthelflæd, cross in hand, muttered a prayer in between her growing heartbeats, but neither fancy trinket nor any prayer would save them this day, she thought.